Buffett, Draper, & Partners

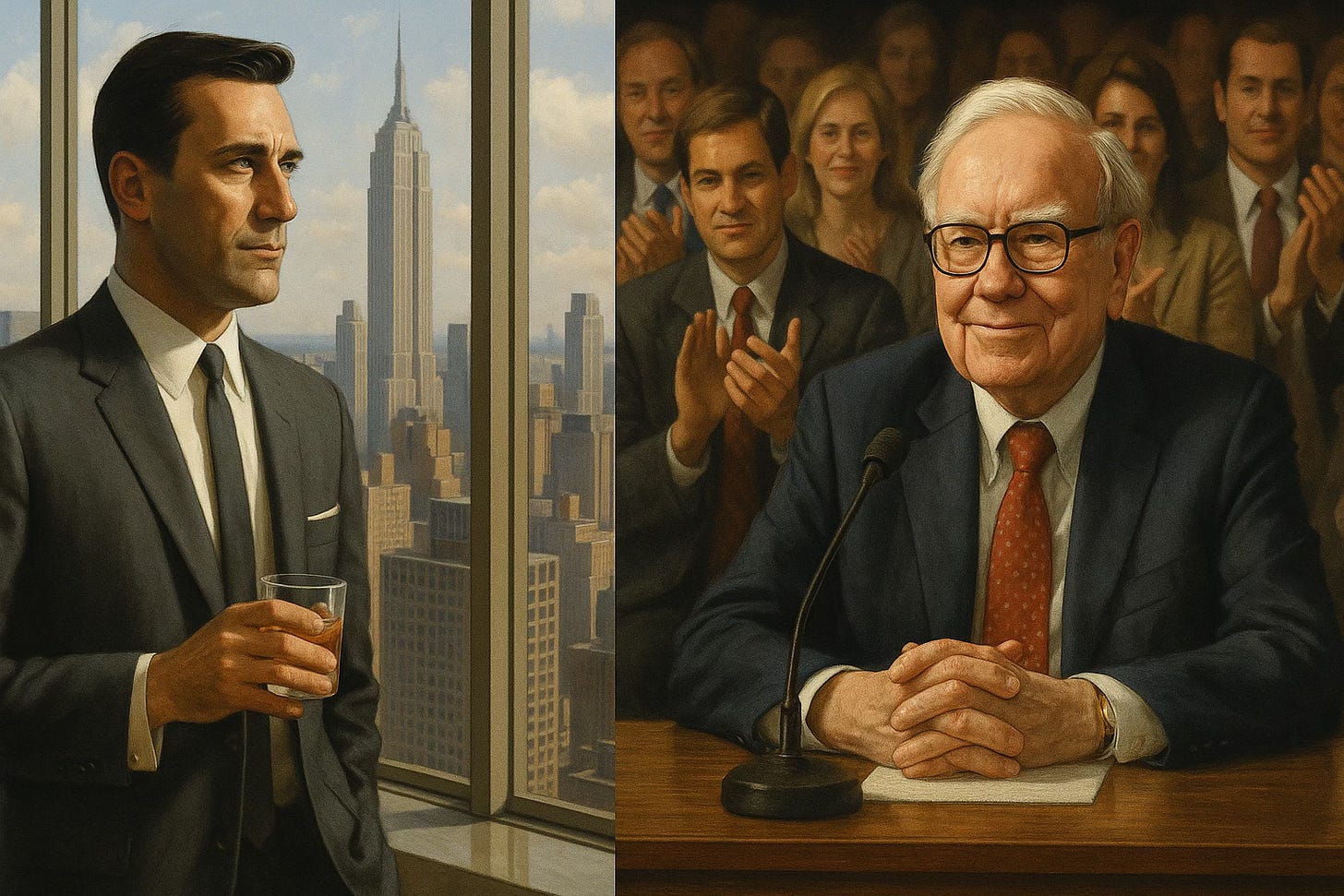

Mad Men and Berkshire go head to head on my first trip to Omaha

I recently finished Mad Men for the first time, a series that masterfully chronicles the main character, Don Draper, against the backdrop of 1960s New York advertising. Draper appears to be the perfect Madison Avenue executive—a mysterious, James Bond-type creative genius whose glamorous world of cocktails, affairs, and high-stakes pitches masks a deeper truth. Through seven seasons, his carefully constructed identity slowly crumbles as the cost of maintaining his facade becomes unbearable. The show poses a haunting question about the price of success and identity: what happens when the mask you wear to succeed begins to destroy the person underneath?

This year, while preparing for my first Berkshire Hathaway shareholder meeting in Omaha, I found myself simultaneously re-reading Alice Schroeder's biography of Warren Buffett, The Snowball, and finishing the final seasons of Mad Men. Over several months, I became entwined in the parallel trajectories of these two men. Despite one being fictional and the other real, both men occupied the same psychological space in my conscious, and held cautionary tales about the hidden costs of American success.

While Mad Men explores character psychology against the backdrop of social upheaval, The Snowball reveals a different kind of ruthlessness—one cloaked in folksy Midwestern charm. Schroeder's portrait shows Buffett as relentlessly aggressive in his early years, barging into shareholder meetings and pressuring CEOs to liquidate their companies. As Schroeder notes, "Surely people realize that he didn't get where he is by running a philanthropic institution." Behind Buffett's grandfatherly public image lay a calculating businessman.

Despite their different worlds—advertising versus investing—both men followed some strikingly similar patterns. As their wealth and professional status grew, they increasingly neglected their families, leaving childcare entirely to their wives. Success brought fulfillment in its own right, but also profound hiccups in their personal life.

While Don battled self-doubt through alcoholism and affairs, Buffett's personal challenges were more subtle—a singular obsession with work and money that became the lens through which he viewed all relationships. Money was how he connected to the world, but it couldn't bridge the growing distance from his family.

When his wife Susan suddenly left him to move to San Francisco, Buffett offered a rare moment of vulnerability:

“It was preventable. It shouldn’t have happened. It was my biggest mistake. Essentially, whatever I did in connection with Susie leaving would be the biggest mistake I ever made…”

“You know, my job was getting more interesting and more interesting and more interesting as I went along. When Susie left, she felt less needed than I should have made her feel. Your spouse starts coming second. She kept me together for a lot of years, and she contributed ninety percent to raising the kids. Although, strangely enough, I think I had about as much influence. It just wasn’t proportional to the time spent.” - The Snowball

It’s an admission of guilt. But what made the characters so compelling on Mad Men, I saw a glimpse of here. There was always a subtle difference between what Don would say and the actions that he took. It could have been Buffett’s biggest self-admitted mistake, but would he have done it any differently?

The costs on their own finally became clear:

While he was friendly enough with his kids, he hadn’t really gotten to know them. The reality behind the jokes (“Who is that? That’s your son”) meant that he would spend the next few decades trying to repair these relationships. Much of the damage could not be undone. At age forty-seven, he was just beginning to take stock of his losses. - The Snowball

This pattern of professional success at family's expense defined an entire generation. But then there’s Greg Abel, Buffett's chosen successor, announced at this year's conference. And he represents a different model entirely. From the Omaha Sun profile of Greg Abel:

“Despite managing global operations that require constant travel, Abel reportedly never missed one of his son's hockey games last winter—including seven out-of-town tournaments.”

A few days after I arrived at Omaha for the conference, I walked through a vibrant riverfront park where children skated and families gathered for sunset. I learned this space existed because of a $50 million donation from Susan Buffett—Warren's daughter—allocated with specific terms in how the money was spent. Even in philanthropy, the Buffett family's story of distance and attempted reconciliation played out.

Perhaps this represents Buffett's own evolution. His children have become central to his wealth distribution philosophy and his life at 95, suggesting he's learned something about connection that pure capital accumulation couldn't teach. The student—Greg Abel—may indeed be learning from his master's mistakes, not just his successes.

How much is enough?

Money “could make me independent. Then I could do what I wanted to do with my life. And the biggest thing I wanted to do was work for myself. I didn’t want other people directing me. The idea of doing what I wanted to do every day was important to me.” - Warren Buffet from The Snowball

There’s a lot of things that drew me to Omaha. Having three friends tag along certainly helped. But at its core, there was something special about seeing a man who’s been so revered in person. The Messiah. The GOAT.

Walking through the Berkshire conference, I was struck by how everyone inhabited Buffett's world completely. Every direction I turned my head I saw, old, white, and mid-western shareholders drinking Coca-Cola, buying furniture at Nebraska Furniture Mart, and discussing value investing as gospel. This wasn't mere brand loyalty—it was Buffett creating a business ecosystem that perfectly matched his worldview.

Something about witnessing this shattered my brain. Here was someone who had never compromised his core personality and his idealism. He chose insurance because he could invest the float without answering to traditional investors. He rejected taking over the Ben Graham Partnership in NYC to build his own empire in Omaha. By the end of the trip, I realized I was witnessing something rarer than financial success: someone who had carved his own path and succeeded entirely on his own terms.

As I sat in the auditorium watching the 95-year-old answer questions from people around the world, I realized that many of us in the audience had consciously chosen lives avoiding the biggest mistake that Buffett admitted he has ever made. But when thousands rose in thunderous applause to give a standing ovation, I felt a sense of happiness to just be in the same building as the man himself.

Buffett was the culmination of a life lived entirely on one person's terms, regardless of the personal cost. How would I imagine my own 2050 shareholder meeting play out? Would it be full of Dairy Queen desserts and endless shopping? Or a vision of a park day in Golden Gate Park filled with carnival games and pickleball tournaments, food trucks and surfing competitions at Ocean Beach. A relaxed Q&A where friends, family, and shareholders discuss not just investment wisdom but how to live a well-balanced life.

I’ll end with this quote from Alice Schroeder, who in a Reddit AMA mentioned a touching moment with Buffett from her time writing his biography when she was struggling with her life at 47.

Warren sat me down.” He said,

Look, when I was 47 I thought my life was over. Susie had left me, and I had already accomplished everything I thought was worthwhile as an investor. Berkshire, as far as I knew, was at its peak.

And to my surprise, my life kept getting more and more interesting since, and most of the really important things I've done happened after I was 47 and thought my life was over.

The reason, he said, was that he had stored up so many experiences, good and bad, in the first part of his life, and as a form of compounding, their positive consequences unreeled over the next thirty-some-odd years.

The snowball compounds.