How long should you spend managing your finances?

Whatever it is - it should probably be more than 1 hour a month

I spend an above average amount of time thinking about money. According to this article, the average American spends less than 2 minutes a day on their personal finances. So by just writing this Substack post, it puts me ahead of most Americans for the year!

But I do more than just write about money. I track my credit card transactions weekly and my net worth monthly. I forecast Interview Query’s business revenue quarterly. Lately I’ve been checking Coinbase almost daily. And every few days I’ll look at the S&P 500 and wonder if I can time the dip.

And the result is that I’m 99% sure I’ve beaten the market in the last 10 years.*

I’ve gotten lucky. I rode BTC and ETH through three boom and bust markets and happened to buy and sell rather fortuitously. I bought stocks in tech companies that I wanted to work for in college because they offered free food.

But most importantly, I actually had money to invest because I was cognizant of wanting to save. And while I think Ramit Sethi in all his wisdom is probably right to stop worrying about $3 problems and start worrying about $30K problems, it abstracts away that the people who freely spend on $3 problems don’t really get to the point of the $30K problems.

But at what point does the time spent on your long term investments outweigh everything else that you do?

That extra 1% edge

Let’s say for the sake of argument that you have a magic genie that grants you an extra 1% better return on your money than the S&P 500 for 30 years straight.

This would be an insanely lucrative genie if you ran a hedge fund managing billions of dollars*. But what if you’re an average Joe and you’re projecting how much you might make with this genie?

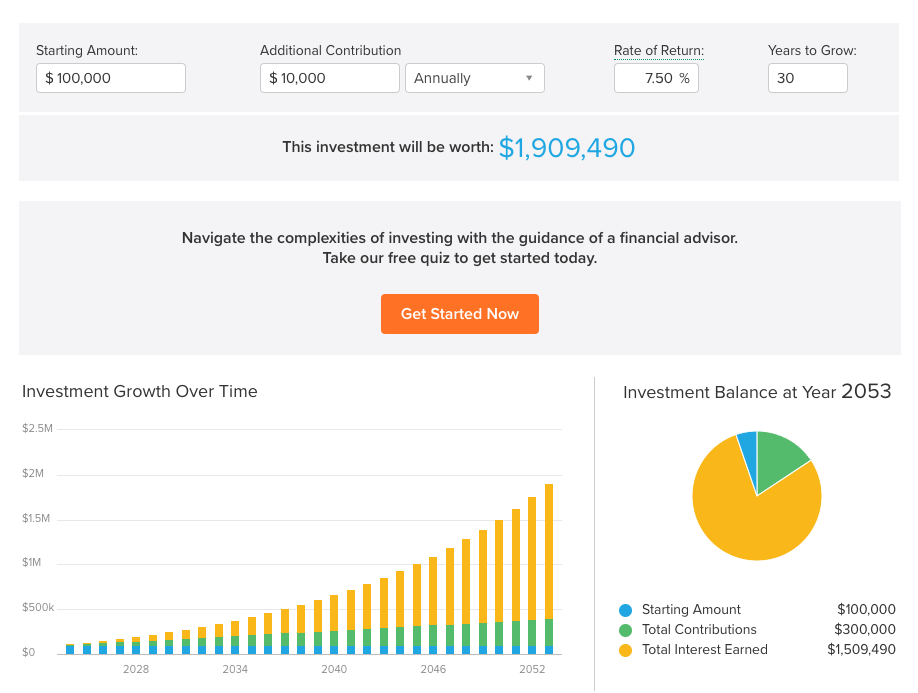

Well let’s do a simple projection. If we adjust for inflation - the S&P 500 has returned on average 7.44% over the last 100 years including dividends. If we round this to 7.5% and then calculate the return with a starting amount of $100K with $10K invested every year for 30 years at a 7.5% compounding rate → we get $1.909 million dollars.

But let’s say we have the genie. An extra added 1% return of 8.5% over 30 years with the same inputs gets us to………$2.426 million.

It’s a 25% increase and an extra $500K over 30 years!

But for the average Joe, if you’re financial savvy, you might realize that this genie might not be that big of a deal. You could easily get your own genie today by just getting a raise or cutting costs to your personal spending.

For example, if you managed to scrimp, save, Venmo request yourself to saving an extra $5K/year, you could invest now $5K + $10K = $15K/year towards investments. And after 30 years at a 7.5% index fund return, you would now earn→ $2.529 million dollars.

But let’s think more practically. Let’s say that you’re an ambitious person and it’s more likely that you can 5x your investment savings from $10K/year to $50K/year by just increasing your salary and keeping your expenses relatively fixed like Ramit Sethi says. Now let’s run the math on this again with the added marginal $5K/year of savings.

$100K starting with an additional $50K/year compounded at 7.5% = $6,045,466

$100K starting with an additional $55K/year compounded at 7.5% return = $6,562,463

$100K starting with an additional $50K/year compounded at 8.5% return = $7,366,561

So now the case for getting a slightly less expensive apartment (or credit card churning to $5K in vacation credits) would give you a 10% increase over 30 years while focusing on outperforming the S&P 500 consistently by 1% would yield a 25% return. Still some people would say - well if it’s $6 or $7 million now after 30 years, what difference does it make?

Now let’s pretend you’ve been working for some amount of time, gotten a windfall from some NVidia stock and you’re starting at $1 million now. Your boss says you’re killing it at work and over time could get promoted into a role with a lot more responsibility (aka stress) and money. You consider their proposal but secretly know you have this genie that can grow your money faster.

You run some quick calculations.

Mid-Salary Joe no Genie:

$1 million starting with $50K/year at 7.5% return = $13,924,925

Mid-Salary Joe with Genie

$1 million starting with $50K/year at 8.5% return = $17,768,988

High-Salary Joe no Genie:

$1 million starting with $300K/year at 7.5% return = $39,774,776

Okay it’s probably worth working your ass off to take the promotion.

But let’s say Jensen Huang is a god (he might be) and your shares 10x again.

Rich but Mid-Salary Joe:

$10 million with $50K contributed yearly at 7.5% = $92,719,522

Rich but Mid-Salary Joe with Genie

$10 million with $50K contributed yearly at 8.5% = $121,793,253

High-Salary Joe:

$10 million with $300K contributed yearly at 7.5% = $118,569,373

At this point, with $10 million already in the bank, it sounds like there’s more of a benefit to becoming an active investor.

So is it realistic to beat the market?

There’s this great passage from the book More Money than God. Buffett was invited to a talk at Columbia to challenge a finance academic named Michael Jensen on the efficient market hypothesis, which posits that current stock prices reflect all available information making them fairly valued. Jensen, arguing in favor of the efficient market hypothesis, made his argument:

““If stock pickers remain in business, it is only because befuddled laymen have a “psychic demand for answers” about where to invest—and never mind the fact that the answers are worthless. The few money managers who appear to defy the random-walk hypothesis are merely lucky, Jensen assured his listeners. “Sure, some beat the market for five years straight. But if you asked a million people to flip coins, some would flip five heads in a row. There is no skill in coin flipping—and investment is no different.”

Buffett listened carefully and then helped make Jensen’s argument even better by positing that beating the market was like a national coin flipping contest. At the end of 20 rounds of coin flipping, there would be 215 remaining contestants who would have called every coin flip correctly and think they were geniuses. But there would be one catch, if the winners were distributed randomly about the country, their success could be dismissed as luck. But what if most of them hailed from the same city?

“Buffett then argued that stock-picking success is not randomly distributed. On the contrary, clusters of excellence spring from certain “villages,” defined not by geography but by their approach to investment. To demonstrate his point, Buffett laid out the records of nine money managers from the value-investing tradition started by Ben Graham, Buffett’s mentor. Three had worked at the Graham-Newman Corporation in the mid-1950s; the others had been converted to the Graham approach by Buffett or his associates. Buffett insisted that he had not cherry-picked his examples; he was reporting the results of all Graham-Newman alumni for whom there were records and all the fund managers whom he had won over to the value-investing method. Without any exception, and without copying one another’s stock choices, each of Ben Graham’s heirs had beaten the market. Could this be simple fortune?”

At every point in a man’s life, there exists a fantastical obsession that they could quit their 9 to 5 job and just day trade their way to riches. Yet we’ve proven that it doesn’t exactly make sense to do so unless you’re doing it for other people (typical investor job) or that you’ve built yourself a nest egg. But the funny part is that once you have made your $10 million dollars or more, then there’s almost an imperative that you believe you can beat the market, it makes rational sense for you to try!

The hard part is that the random coin-flipper who wins 4 times in a row without studying coin flipping physics and thumb movement dynamics religiously might actually be getting lucky.

And so what does it take to actually be above average in this case? Do you need to spend 8 hours a day for the rest of my life reading earnings reports? Is it about working at a hedge fund for 10 years to learn the secrets of the trade before doing it for yourself?

Consistency is probably key. And beating the index fund by 1% the last 5 years is arguably much more impressive than the first 5 years. But at the very least - a risk adjustment of the portfolio is worth thinking about a few hours every month at the very least. Creating a decision ledger of past decisions to continuously refine my judgement is probably worth doing. And if was sitting on $10 million dollars, using this time appropriately could be the difference between $0 and $30 extra million dollars that I could donate to causes that I care about over the next 30 years.

I’d love some feedback on this from readers. Do you spend time managing your personal portfolio? Do you think you’ll spend more time on it in the future?

Appendix

I haven’t exactly calculated this out - but I’m pretty sure given I’ve calculated my spending since 2019 and I’ve saved my tax returns so I can see what’s been saved / invested. But it’s not perfect and if I really cared - I would sit down and try to figure it out. Or at least make it easier to figure out going forward.

Unless you charge 2 and 20.

I've been obsessed with personal finance, and personal investing since my first paycheck in 2014.

I've tried nearly everything over time:

- day trading

- timing the top/bottom of the market

- obsessively managing my expenses to reduce burn

- etc.

Looking at my portfolio now compared to S&P 500, I've been extremely successful (and extremely lucky) over that time period.

I attribute my success to luckily picking proper macro trends to align to, and not making *too many* dumb mistakes (the most typical one is selling at the bottom).

I've realized over time something similar to you, that obsessing over an additional 1% gain is a waste of time compared to getting a promotion, or generating an alternative form of cash flow to grow my principal.

I'm still recalculating my net worth on a regular basis, but it's much less neurotic. I think my performance in recent years is ironically better than before, because if I look at it less, I'll make fewer dumb mistakes, and incur fewer transaction costs & fewer taxable events.

I tend to only trade crypto these days and only aim to gain on big cycles in the market. If it feels like the market is hot even if it’s not the peak I sell. I buy or sell depending on the log curve trend line of adoption of new technology. Since crypto has an adoption trend similar to that of the internet you have some preconceived notions of how fast or slow user growth will be with there being volatility throughout. You can tell the market is too hot when new people are entering and throwing a lot of money into it. When my electrician who was installing my power distribution for our mining farm said he wanted to purchase mining equipment for $20k it was time to sell. When the news is telling you that something is way down but expect it to get much much worse then buy. Basically being contrarian and doing the opposite tend to always work somehow. Overall most people are thinking “What do I need to have in savings to retire?”. Honestly if you have recurring profits that outweigh your expenses then you can retire much earlier than people think.