Nextdoor's Disappointment

From billions to millions

This is part of an ongoing series of essays to deconstruct the past startups that I’ve worked at and what separates successful companies from failures. Part 1 went over how the first startup I joined, Jobr got acquired for millions in two years. Part 2 was how I failed to build a concert ticket flipping operation.

The week after I signed my offer to work at Nextdoor, I got a text from my friend who worked at Square.

“Holy fuck you won.”

He was referencing the news that Sarah Friar, at the end of 2018, had announced her resignation as CFO of Square, and was now taking over the top role at Nextdoor.

She was a beacon of hope for Nextoor, a business that had scaled to tens of millions of users but had recently stagnated. Her job was to replicate what she had done at Square, transforming the company over the previous five years to becoming a $50 billion dollar payment behemoth. Nextdoor was obviously in a different market, but it was primed for growth, and the story was that Friar could take the company from a one billion dollar valuation to a $100 billion public company that was the de-facto neighborhood social network.

Seven years later and it’s clear that those aspirations have now fell flat. Nextdoor, now publicly traded, is at a lower valuation than when I had first joined. Most employees have liquidated their shares, at a fraction of what they had thought they would be worth. And the old CEO, Nirav Tolia has come back into the driver seat, and after one year, cannot shake the tepid reputation that has lingered on Nextdoor. Sarah Friar herself has fled to OpenAI, back into her comfortable seat of CFO.

My experience and information is six years plus dated. I have not tried to keep up with the latest in the company. But the early warning signs were there, and worth revisiting as a cautionary tale of failed promise and ambition.

Why I joined Nextdoor

After two years of working in data science at Monster, I started freaking out. The original startup team was slowly being replaced by employee bought into the new corporate culture. The people telling us what to work on were run of the mill corporate goons. And one by one, the friends that I had spent my post-college formative years with, had decided to leave the company. And quickly realized I would be heading in the same direction. So I started interviewing around at new companies when I eventually got a message from a company called Nextdoor.

The company was around 200 employees and in the awkward teenage stage of startup life. While it had matured out of its initial scrappiness days and plateaued out of its initial hyper-growth phase, the hiring of Sarah Friar was a new inflection point in the company’s history. Friar had scaled Square and was rumored to be one of three people under consideration to replace Dorsey, who at the time was running both Square and Twitter as CEO.

I was joining a data science team of around 5 to 6 people that was going to triple in size after a year. And what I immediately noticed in the interview was how much culture mattered at Nextdoor. The neighborliness accentuated in their mission statement trickled down into the work culture and each person I interviewed with. There was a clear prioritization of work life balance and a no assholes priority in the hiring process. While my last company’s motto was that revenues and growth came first and culture would eventually follow, I had seen the fallout once our company was acquired and revenue didn’t matter (P.S. there was also no culture to be had).

But looking back, I realize that it’s important to understand if that was the pivotal reason why I decided to join the company. Was I joining Nextdoor because I had burned out of seeing the same weird corporate engineering guys repeatedly in an open office space? Was I looking for some data science solidarity in a team environment vs being the only data guy? Or was I truly trying to make money and join another growth startup that was this time going to 100x?

I don’t think I looked truly understood the tradeoffs when I signed my offer and decided I wanted a job that would mix work, community, and potential upside. Maybe Nextdoor wouldn’t 100x in the next 4 years, but they could 10x right? And with hindsight, there were probably a few early warning signs.

What Matters at Bigger Organizations

At Jobr, if I wanted to chat with the CEO, I would turn around and stand up. At Nextdoor, it was clear that there was no reason for me to chat with the CEO. Bigger companies, even startups, come with layers of management and org structures, with each person taking on their defined responsibilities.

My responsibilities were to onboard onto the real estate monetization team at Nextdoor as a data scientist. Nextdoor monetized realtors through subscription ads, where each realtor would fractionally “own” advertising slots on Nextdoor by zip code. The pitch was that the realtor’s face would be rotating on Nextdoor’s version of Redfin and Zillow as homeowners and renters browsed houses for sale in their neighborhood.

We were also allowing Nextdoor members to message the realtors. And while in a perfect world these would be hot leads in the form of members looking for realtors to help them buy or sell homes, realistically it was a lot of people selling services to realtors, which inevitably turned their Nextdoor inbox into spam.

So one project I was tasked on was building a model to predict whether the messages sent to the realtors were spam or a lead. This involved parsing out the dataset of messages to realtors, isolating a precision recall frequency that was ideal, and then rounding up the whole team during lunch to help hand label the messages. It was a cross functional machine learning project that I deployed with the engineering team. But after it was shipped, and realtors got less spam in their inbox, not much happened. The value was slow, our project was a retention play versus a more realtor acquisition strategy to help sales. And when finally the project was presented at all hands to some mute applause, I was realizing it was now extremely difficult to also quantify correctly the impact and performance of what I was doing.

And so one day, I decided to write about it. My data science manager somehow had access to emailing all@nextdoor.com, an email alias that quickly got shut down to non-managers after Friar joined. But since we had a data science blog, my manager circulated the writeup I made about the project to everyone in the company, and surprise, executives actually read their email. Soon after the CEO + executive team reached out to congratulate me directly.

This catapulted me into what could only be described as an internal data science team fame. Our entire data science org would now write up blog posts on their projects after seeing the success I had in circulating that first memo. And I gained more leeway to work on any project and switch teams to wherever, a few months later.

This taught me something about bigger startups. If I ended up working on a project that made a big impact at the company, then I would be rewarded. But it’s hard to find those inflection defining projects where you might create Gmail at Google or the infamous “people you might know” feature on LinkedIn. Most improvements are small and incrementally add value over time.

At the end of the day I realized that data science can easily fall into a support driven role, and there are really two things that provide lasting legacy for any organization: doing an analysis that reaches the highest level of decision makers to increase leverage, or building engineering projects that contribute to substantial revenue or cost savings to the company. But quite concretely I noticed my work followed into the former, where I could generate more goodwill, respect, and circulation of my work by writing about it than actually increasing my SQL query or coding output. With that in mind, I did have some product leverage on my decisions. Now it was only a matter of what to do with it.

The difficulty of expanding from initial product market fit

Slowly throughout the year, Nextdoor was growing to scale. We were doubling the headcount of the business and hiring new people every week to the point where we even stopped traditions with new hires that would take too long at all-hands.

But revenue goals were still being missed. In 2019 there was an ambitious goal to hit $100 million in revenue. Growth was happening but it was slow and linear, not exactly exponential to the right. We were placing a lot of new bets in features like groups, events, and real estate, but things moved slower as we expanded headcount.

And slowly, my personal disillusionment grew from the fact that by six months in, there was clearly no path or feature that I could work on that would 10x the business. And even if there were, I wouldn’t be making those decisions no matter how many analyses I made. Friar had now settled in and the old executives had already left and new ones were brought in from companies like Square, Facebook, and more.

Nextdoor at that time, presented itself as successful for being a neighborhood social network where neighbors could chat, meet each other, coordinate events, and giveaway free items. And yet the prime reason Nextdoor worked was because neighbors had a core necessity of wanting to feel safe in many of their neighborhoods.

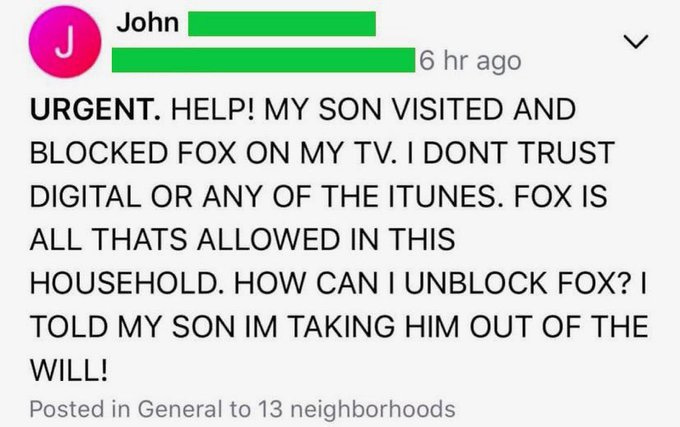

But because there was such an anti-neighborhood policing attitude at Nextdoor, it was very hard to lean into the safety aspect as Ring or Citizen were doing. Ring, one of Nextdoor’s biggest ad sponsors, had a community social app which allowed neighbors to post Ring camera footage at their front door of anything suspicious. Citizen allowed their users to report and see dangerous activity around them. But Nextdoor had generally retreated from this mission around safety after getting backlash from users racializing suspicious activity, and in trying to curb those effects, wouldn’t build features into much of our core demographic.

What was our core demographic? One day, I decided to integrate some census data into our neighborhood dataset. By joining a dataset showcasing Nextdoor usage and member penetration rates (% of the neighborhood on Nextdoor) with zip-codes and their overall demographics, it clearly showed a high correlation use of Nextdoor with pre-dominantly white neighborhoods and low correlation use with black or high latin / Mexican penetrated neighborhoods, even when adjusted for income.

So it was pretty clear white old ladies loved Nextdoor, aka Karen’s. And yet the company couldn’t grapple with it very well. This was clearly why Nextdoor dealt with community moderation, long threaded arguments, and heated debates between firework lovers and dog owners. And many times it was very hard to build upon that individual customer profile because it was socially frowned upon to only support their needs. In many ways the mission was different, but what actually built the company was the use case of making sure old white people bonded better together. And that wasn’t okay for anyone at the time. Nor was an easy thing to accomplish.

Why I ended up quitting

At the end of the day, it was clear that what I was doing at the company didn’t align with my personal goals. The mission of the company was ambitious, but by the end of my first year we were a 400+ person company, and my job was to be a despondent data scientist.

When your heart isn’t in the product, or the company anymore, it’s much harder to work through the problems. And that feeling as an individual contributor is one that I believe a lot of people do have at large companies, which is no real empowerment to make product decisions or changes that make an impact.

Yes I feel like most people have to do their time to get there. But I was also kind of impatient. I did a one year tour of duty to get my stock options. And in the years after I left and right before they IPO’d, my stock options became potentially worth 5x of what I purchased them. My old co-workers and I were ecstatic, greedy, didn’t sell (mostly because we couldn’t in the six month lock), and watched them go down post-IPO to a price that was below even the valuation that I joined at.

You can blame management, you can blame the CEO, but at the end of the day, fundamentally the product couldn’t find a way out of its trap of existing users. Value creation is hard work and culture is the permeating factor that keeps these products alive.

I wasn’t around for the rest of their growth pain. But I think it was quite clear that there were certainly tons of pains towards getting to a path of hyper-scale in a model where almost all software engineers and data scientists left the company for jobs at Meta or Roblox.

At the end of the day it was the perfect stepping stone for me and many other people in their careers. It functioned well for the job hoppers and not so well for the lifers. I cannot see an exit path for the company in its near future. But maybe it can just accept its path as existing in it’s own space and serving a niche need.

That's an interesting case, where there *is* PMF but it is misaligned with the ethos of the company.

Your experience writing about your data work is good inspiration for me! I haven't really done that internally.

Thanks for sharing!